Want to read about some adventures? Would you like to meet an unknown super hero? Let me introduce you to Nellie Bly….

Her real name was Elizabeth Cochran, and she was an important pioneer of modern investigative journalism. We're in the last years of the nineteenth century, though: they called this style of reportage “stunt journalism.” This was a practice, where someone in the news biz would throw themselves into a story--literally body and soul.

Nellie’s adventures were incredible, and the lengths to which she would go to investigate a story so great, that I think modern journalists like Woodward and Bernstein have a great debt to lay at her door. But, as usual, very few remember her name.

It was Nellie who went into a NY state insane asylum under cover as a patient, in order to accurately report on its' conditions. It was Nellie who broke Jules Verne's (Philleas Fogg) fictitious record of travelling around the world in less than 80 days. And, she did all of this at the tail end of the 19th century, alone.

Have I whetted your appetite?

Alright, Dear Reader, let us begin.

Like always, I like to provide you with visuals:

Elizabeth Cochran was born in May, 1864 in the township that bore the name of her family: Cochran's Mills, PA. When she was about six years old, her father (Michael Cochran) died intestate. This left her mother and siblings without support, and so they left town. In the late 1870s, Elizabeth's mother remarried, but it ended in dissolution, due to systematic abuse.

After 1878, Nellie enrolled at the State Normal School, in Indiana Pennsylvania. Because of financial constrictions, she was only able to stay for one semester. Afterwards, the family had to move to Pittsburgh, and Nellie started trying to look for work, in an effort to help support her family.

She was unlucky in her search for employment, while her brothers were all able to find jobs. Gee, I wonder why? One day Nellie read an article in the local newspaper, The Pittsburg Dispatch. The piece criticized the presence of women in the work force. Pissed off, she wrote a letter to the editor protesting the article, stating that if women were given equal opportunities, they would meet any challenge. But, the editor refused to give her stories that spoke to everyone, rather than to simply one audience.

So, she left the paper, and left town.

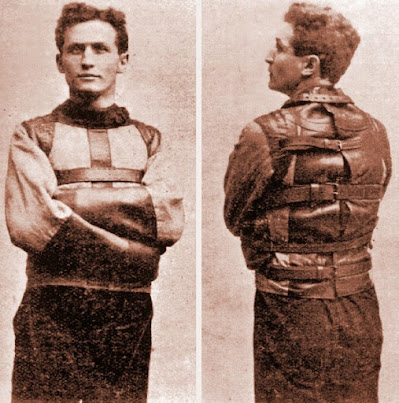

Nellie finally landed in NYC, 1886--this was the nerve center for news at the time. Predictably, it was incredibly hard for her to find a position with any paper. One year later, though, she was still without a position. Rather desperate, she bludgeoned her way into the office of none other than Joe Pulitzer, publisher of the New York World. At this time, Pulitzer's newspaper was one of the most popular publications in the country. While he was not about to hire her on the spot, ole Joe liked her spunk. He decided to challenge this charismatic young woman, telling her that if she personally investigated conditions in a mental institution, and wrote about treatment, then he would consider giving her a job. Oh, but what hospital? How about, the most notorious mental hospital in the country, Blackwell's Island?

What did she say? 'Hell yes!' Well, sort of:

I had some faith in my own ability as an actress and thought I could assume insanity long enough to accomplish any mission entrusted to me. Could I pass a week in the insane ward at Blackwell's Island?

A brave woman.

Back to our story....

Nellie, pretending to be mentally ill, appeared in court, and was duly committed. Don't worry though, ole Joe (Pulitzer) knew all about it, and kept a weather eye on his new recruit. Immediately upon her entry into Blackwell's Island for Insane Women, Nellie began to witness horrors (see above). She also experienced the depersonalization of patients. I am sure that you can see the dangers inherent in this approach by the staff. As previously stated, she came away with an overarching impression that the asylum was in fact a huge dispose-all for society's unwanted--whatever their circumstance. Nellie saw, almost at once, that no one seemed to care about these forgotten souls, and now that she was (temporarily) one of them, began to witness the horror of their lives. She saw the importance of public awareness--perhaps then, there might be substantive changes in treating the mentally ill.

Her descriptions of the horrifying conditions were dramatic:

I would like the expert physicians who are condemning me for my action, which has proven their ability, to take a perfectly sane and healthy woman, shut her up and make her sit from 6 A. M. until 8 P. M. on straight-back benches, do not allow her to talk or move during these hours, give her no reading and let her know nothing of the world or its doings, give her bad food and harsh treatment, and see how long it will take to make her insane. Two months would make her a mental and physical wreck. Nellie Bly, "10 Days in a Madhouse."

Nellie encountered different patients, who had been committed for various reasons. She found a large number of sane but unwanted women, many of whom were committed by their husbands. Yes, a man could do that in those days. There was no such thing as a patient's "bill of rights."

A pretty young Hebrew woman spoke so little English I could not get her story except as told by the nurses. They said her name is Sarah Fishbaum, and that her husband put her in the asylum because she had a fondness for other men than himself. Nellie Bly, same title.

I would have enjoyed giving Sarah's husband a few sharp objects to play with.

Patients were regularly beaten, and verbally abused by the attendants. In addition, inmates were given spoiled food to eat, bedding riddled with insects, and freezing temperatures. It is no surprise, that in such conditions, a healthy person would begin to suffer physically, and then mentally. Abuse is abuse.

Immediately upon admission, Nellie began talking with fellow patients. She also began acting and speaking normally (to no avail). She quickly discovered that the hospital was indeed a hell into which the impoverished, foreign, and unwanted women of society were dumped. Once there, these women had no advocates, no compassion, and no escape.

Finally, her would be boss at The World sent his lawyer to court to petition her release. This was easier said than done, but eventually she was freed. By October, 1887, Pulitzer published the first installment of her medical adventures. It was an instant public sensation, and the story quickly became nationwide. She eventually published her serialized articles in a book, unimaginatively entitled "10 Days in a Madhouse."

Nellie's stunt reporting was so successful, that other women reporters tried to capitalize on her success with stunts of their own. So called "stunt reporters" were able to get the 'skinny' on civic institutions, opium rooms, so-called 'sweat shops,' and even illegal abortionists.

* * * *

You'd think that her adventures would have been over, relatively, and that Nellie subsequently settled into a journalistic career that didn't require her to be incarcerated. But, you would be wrong, folks. Nellie quickly bounced on to her next adventure: beating the fictional Philleas Fogg's record of travelling around the world in less than 80 days. This was a story that captured the imagination of Western audiences in the late 19th century. While many believed Fogg's journey to be possible only in the realm of fantasy, Nellie was determined to prove them wrong. The New York World accepted her proposition, and she was on her way.

Comments

Post a Comment