The last stand of Custer, the seventh cavalry, and the horse cultures of the great plains...part one.

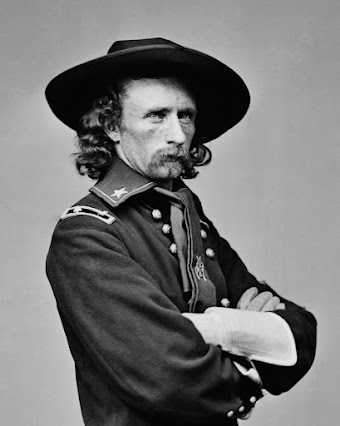

He did serve in the war with distinction, displaying his bravery (uh recklessness). Yes, reckless. And his poor horses! He had more horses shot out from under him, than any other cavalry officer in the Civil War. As a recognition of his action in the field, Custer was made something called a "brevit" general. He was 25. Now, this was not a real promotion--he retained his rank of major, while at the same time having attained the temporary status of general. But this is a pretty young age, to attain such a status (albeit temporary). That is what the term 'brevit' means. In our western history, you might have heard of him as "general Custer." That was an honorary title, and nothing more--he was still a colonel, even at the time of his death in 1876.

Custer was both loved and despised by the men under his command, in the war ( and after). Such attitudes were indicative of the rest of his military career. Always a figure of controversy, was our golden haired boy. But, he quickly became infamous for the strict enforcement of military regulation, which forbade destruction of private property, looting, etc. At the end of the war, Custer was assigned to the command of Philip Sheridan, and set out for Texas. Their mission was to prevent Confederate soldiers from escaping into Mexico, and somehow retrenching for another attack (??? Like they could have, by 1865). He served there for five months, finally mustering out by 1866. He had ten years to live.

By 1866, Custer was made a lieutenant colonel, and put (relatively) in command of the now famous Seventh Cavalry. His new posting put him squarely in the middle of another crisis of the country: the plains Indian wars. There he encountered hostile action from several tribes: Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa, and Arapaho.

But, Custer was headed for trouble, for he regularly operated outside of the moral code established by the U.S. army, often treating his men in an offhand, arbitrary manner. Thus, we see one of the troubling aspects of his character: hypocrisy. In 1867, Custer was court martialed. This would be one of the many times that he found himself in trouble with his superiors.

At length, he was reinstated. By 1868, he was back in the saddle, leading more raids against the Cheyenne. I suppose it was inevitable that sooner or later, he would get into trouble again, and so he did.

It was called the Battle of the Washita, and took place in November, 1868.

This engagement involved the 7th, who acted as one of many on this particular expedition. The goal was to force the tribes, who had left various reservations, back into their prison. Custer drove his men hard in that harsh winter, finally finding a fairly large group of Cheyenne (and a smattering of other plains' tribes), encamped by a bend of the Washita River, in what is now Oklahoma.. Leading the group, was Black Kettle, a survivor of Sand Creek (more later, but if you cannot wait, you can find out about it by clicking on this link: sand creek On the morning (well, dawn really) of the attack, Custer wanted to take the village unaware, which he did. He ordered his men to surround the area of the "enemy" on both sides, effectively possible avenues of escape. His orders were quite vague when it came to the treatment of the indians they came across, so you might imagine, leaving their fate rather uncertain.

You might imagine what happened next. Yup. Slaughter. Very few of the native peoples survived the encounter.

The thing that gets me, was how Custer ordered the bugler to play his favorite song, "Gary Owen," to signal the attack. Asshole. I bet you'll recognize this tune:

It was the song he always played, before the attack. A jaunty tune, it came to have a darker meaning, by the summer of 1876.

At the beginning of the hostilities, Indians fled for cover. It was a massacre, as you might imagine. Now, one of the tragic facts about this battle, is that members of the Osage tribe led Custer and his men to the village. One of their traditional enemies were the Cheyenne. It was just another instance of the white man using existing enmities against the so-called "opposition." But, don't you worry--the Indians would have their revenge (albeit a brief one), in July of 1876.

In spite of the 'pincer' attack, which enabled a successful raid, Custer was taking a big risk--what he didn't know (or perhaps didn't care), is that there were other encampments further along the river, and what amounted to hundreds of natives. He and his men could have met disaster there and then, but they didn't. In that moment, something that his men called "Custer's Luck" was with them. They survived, but many of the natives did not. In the aftermath of the battle, Custer would claim that his command was responsible for the deaths of 103 warriors.

Bullshit.

Warriors. What they did do, was to butcher mainly the old, women, and children. But, you must understand, warriors were more "valuable" victims from the perspective of the government. In point of fact, the number of dead was never calculated. But, there were losses among Custer's command: a company of men under Major Joel Elliot, who during the battle found themselves isolated from the rest of the soldiers. Custer was aware of the absence of Elliot's command, but he did nothing, leaving them to their fate. Custer would later claim, that Elliot separated from the larger group without his order. Whatever the case, he left the field, without ascertaining the fate of the missing soldiers.

What a guy.

The loss of Elliot's command had a direct effect on Custer's relationship with his men: something that was enflamed through the efforts of one of his junior officers, Frederick Benteen, who had been a close friend of Major Elliot.

Remember the loss of Elliot's command, when we make it to the final stand of George Custer, ok?

Alright, that's it for part one...if you want to, continue on to the next entry, to find out Custer's fate, that is, if you don't already know it.

Comments

Post a Comment